Liveblog by Beyang Liu (@beyang)

Update: slides for this talk have been posted here.

Improving operations in Go programs

Ian Schenck, software engineer, Infrastructure at Oscar Insurance (ian.schenck@gmail.com). “I am a SWE who ends up in SRE.”

Ian tries to write operable code. In other words, he assumes it’s going to break at some point and tries to make it easy as possible to diagnose what went wrong.

This is operations in a nutshell:

The Software Design Life Cycle (SDLC):

- Plan

- Analyze

- Design

- Implement

- Document/Test

- Maintain

- Repeat

(but not necessarily in this order)

Almost always, you have to deal with broken code you didn’t write in this cycle.

The importance of maintenance

When a piece of software fails, you should have two equal objectives:

- Fix it

- Determine what went wrong

The second goal is often overlooked. In order to achieve it, it’s important to “fail well.” What does “failing well” entail? A few things:

- fail immediately when unrecoverable errors happen

- fail only the smallest execution unit necessary

- but err on the side of failing an entire operation (maybe the whole application) rather than continuing in a corrupted state

Unhandled or unrecoverable errors should typically panic in Go. In doing so, you should strive to provide clear, concise info about the panic’s cause.

Diagnosis via 5 whys

Five Whys is a process to get to the root cause of a production error. The idea is if you ask “why” 5 times, that will lead you to the deeper root cause of the issue.

In order to do 5 Whys effectively, you need to have a lot of information available that you can use to answer each of those “Why”s.

Here’s some good sources of information to aid your diagnosis:

- Stack trace. SIGQUIT (

kill -3) is your friend - Logs (specifying action, with context)

- Environment

- Flags

expvar

Logging

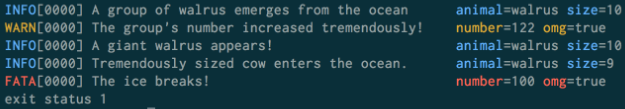

Structured logging is nice. It makes it easier to scan, analyze, and filter your logs.

You can do structured logging with https://github.com/sirupsen/logrus:

log.WithFields(logrus.Fields{

"animal": "walrus",

"number": 8,

}).Debug("Started observing beach")

Here’s an example of structured logging:

A note on logging errors:

Some errors provide good context. For example

listen tcp :33712: bind: address already in use

“Named” errors do not:

unexpected EOF

How do we know what to log, how much to log, when not to log? How do we deal with “Logging Anxiety”? Is there another way to expose this information? Well…

expvar

Beyond logging, how can we expose useful information in production?

expvar is a standard library package that lets you specify the current state of the application. This includes:

- cmdline info

- memstats (allocated bytes heap/sys/total, GC stats, allocations by size)

It exposes this information via a HTTP handler that returns data in a form that looks like this:

{

"cmdline": [

".\/expvar_example"

],

"memstats": {

"Alloc": 136736,

"TotalAlloc": 136736,

...

}

}

You can also specify your own state via the Publish method, which accepts a Func that returns an arbitrary interface{} that is then marshalled to JSON in the expvar HTTP endpoint:

func init() {

http.HandleFunc("/debug/vars", expvarHandler)

Publish("cmdline", Func(cmdline))

Publish("memstats", Func(memstats))

}

You can use this to expose key environment variables, command-line flags, and even secrets (provided you securely hash the values so you can do equality comparisons without leaking the actual secret to the HTTP endpoint).

Environment variables:

func publishEnv() map[string]string {

env := make(map[string]string)

for _, line := range os.Environ() {

parts := strings.SplitN(line, "=", 2)

env[parts[0]] = parts[1]

}

return redactMap(env)

}

Flag values:

func publishFlags() {

flagMap := make(map[string]interface{})

flag.VisitAll(func(f *flag.Flag) {

flagMap[f.Name] = f.Value

})

redactMap(flagMap)

}

You can also publish stack traces:

func publishStack() interface{} {

buf := make([]byte, 65535)

n := runtime.Stack(buf, true)

buf = buf[0:n]

return string(buf)

}

expvar is complementary to structured logging. Use expvar to describe state. Use logging to describe action.

expvar tips and pitfalls

expvar is very useful, but there are some pitfalls. Here are some tips:

- Don’t publish expensive functions. These can make expvar too expensive and even turn it into an accidental DoS vector

- Use verbose names. Err on the side of greater descriptiveness through verbosity.

Beyond expvar: more operable HTTP endpoints

You can also expose other information via HTTP:

- Health handler

- Specialized handlers for libraries (e.g. Vault integration)

- Shutdown handlers (quit and abort)

- Admin handlers: you can have arbitrary pages up for interacting with the process

- Stats for monitoring, e.g., Prometheus metrics

If you do expose more functionality via expvar, make sure you follow REST conventions, like only do modification/destruction on POST.

Recap

Think about failure at all times to guide:

- Panicking when necessary

- Exposing data via expvar

- Logging and context

- Naming (flags, environment variables, etc.)

Q&A

Q: We’re using logrus to add context automatically when we get an error. Do you recommend adding context at the site of the error or logging higher up in the stack?

A: I tend to go with higher up in the stack. There’s 2 ways to add context: 1) errors.Wrap, 2) log the error with additional context. Both acceptable.

Q: How do you set access policies around these inputs? In other words, do you expose endpoints to everyone who wants to use them or do you bind the endpoints to an interface that’s only accessible by, say, the Ops team. Do you have rate-limiting on the endpoints?

A: Our endpoints are not public to the outside world, but generally, anyone on engineering team can freely hit these endpoints. It’s worked so far without any formal restrictions or limits. We’re a health insurance company, so really sensitive about data, but the approach is working for us so far.

Q: Guidelines for when to structlog/expvar something vs. when to dump it into something like Prometheus?

A: If it’s something countable, put it in Prometheus. If it’s something that’s a struct (more complex), use expvar.

Q: Have you tried exposing pprof info? Do you use it in production?

A: Someone wrote an expvar endpoint that starts a pprof profile and sends you a URL to access the profile output. It’s pretty scary when you do it, but comes in handy.

Q: Do you want the Go standard library to expose any additional metrics? For example, reporting the number of open TCP connections?

A: That’s tough. I worry about unexpected side effects in doing that. I don’t like the side effect of expvar adding an HTTP handler to the default server mux, for instance. I worry about some poor web developer who’s ignorant of it being bit by it. But in general, yes, I think it would be better if libraries exposed their own instrumentation endpoints. And it’d be great if the standard library had that functionality.

有疑问加站长微信联系(非本文作者)